Humanity is witnessing an evolutionary shift in warfare. With economies increasingly relying on big data, software, and connectivity, the damage stemming from cyberattacks can overshadow the impact of traditional military operations. It comes as no surprise that nation-states have been active in this domain for more than a decade, raiding their adversaries with surreptitious hacks, DDoS incursions, and malware. The goals range from industrial espionage and political influence – to large-scale disruption of critical infrastructure.

This article provides a rundown of the most notorious cyber-incidents attributed to governments and affiliated threat actors. These compromises have become a whole new ballgame in the global security paradigm, where financially motivated seasoned criminals aren’t the only players in this arena.

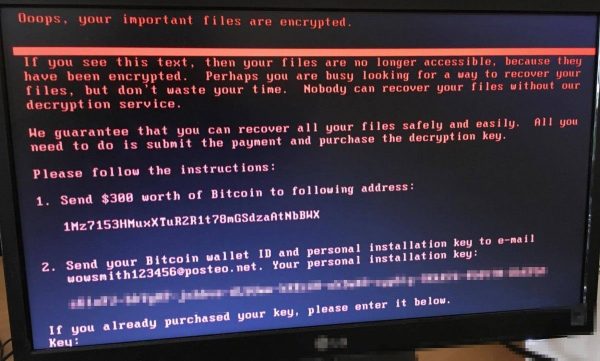

WannaCry

WannaCry, a predatory crypto worm at the core of the most deleterious ransomware campaign in history, fully lives up to its name. This attack took the world by storm in May 2017, hitting more than 230,000 Windows computers in a total of 150 countries. The pest encrypted data on infected hosts and demanded $300-$600 worth of Bitcoin for recovery. Aside from contaminating numerous users’ home PCs, the strain affected a number of high-profile victims, including the UK’s National Health Service (NHS) agency, FedEx, Nissan Motor Manufacturing, Renault, Deutsche Bahn, and Boeing Commercial Airplanes.

There is a strong reason why the WannaCry ransomware became so prolific in mere days. Its operators used a highly furtive distribution mechanism relying on exploits dubbed DoublePulsar and EternalBlue. This way, the infection chain was absolutely covert and users had little to no chance to prevent the attack. The irony is that both of these exploits were reportedly discovered by the U.S. National Security Agency (NSA). A hacker crew called The Shadow Brokers stole and leaked them a few months before the epidemic was unleashed.

The plague was in full swing for about four days. Security researchers stopped its further proliferation by unearthing and triggering a kill switch built into the ransomware code. Additionally, Microsoft released urgent patches for the above-mentioned exploits. Despite the short time span of the attack, the estimated worldwide losses reached billions of dollars. In late 2017, the authorities in the United States, Australia, and the United Kingdom officially blamed this onslaught on malicious actors working for the North Korean regime.

Stuxnet

Zeroing in on complex industrial systems, the Stuxnet worm is really one of a kind. It was discovered in 2010, when a nuclear facility in the city of Natanz, Iran, underwent a cyberattack leading to the destruction of numerous uranium enrichment centrifuges. An unknown infection caused the rotor speed of these centrifuges to increase and decrease iteratively, thus entailing vibrations that literally made the equipment fall apart. This impact resulted from the shenanigans of Stuxnet.

Technically, the threat is a computer worm that spreads laterally across a network and efficiently hides its footprint to avoid detection. It is designed to affect PLCs (Programmable Logic Controllers) constituting SCADA (Supervisory Control and Data Acquisition) systems and widely used to control industrial processes.

When inside a host environment, it specifically looks for PLC computers running Step7 software by Siemens. If Stuxnet finds equipment meeting these criteria, it issues rogue commands to disrupt certain technological processes while continuing to provide normal statistics to the operator.

This sophisticated malicious code spreads through a booby-trapped USB drive, which means it infects systems isolated from the public Internet, such as secret facilities. Furthermore, the fact that it scans compromised networks for software known to be used in Iranian nuclear labs is a telltale sign of a well-orchestrated campaign against a predefined range of targets.

According to several investigative reports published after the Natanz incident, Stuxnet was a product of American-Israeli collaboration aimed at thwarting the Iranian nuclear program. The “suspect” countries never admitted to these allegations formally, though.

NotPetya

In late June 2017, numerous organizations in Ukraine and about a dozen other countries fell victim to ransomware bearing a strong resemblance to Petya, a strain discovered a year earlier. The original infection encrypts the MFT (master file table) and thereby prevents Windows from launching until the victim coughs up a ransom.

However, upon closer inspection, it turned out that the sample spreading in Ukraine was different. It encrypted all data on hosts and provided absolutely no recovery options, which means its goal most likely boiled down to sabotage. Based on this fundamental discrepancy, researchers dubbed it NotPetya.

The perpetrating code was distributed via a trojanized version of M.E.Doc, a tax accounting suite used by more than 400,000 Ukrainian companies. This is how it infiltrated the networks of the country’s major banks, media outlets, ministries, electricity firms, and hundreds of businesses.

Propagation of the plague beyond the targeted country was collateral damage. It hit many organizations in Germany, France, the United States, the United Kingdom, Australia, Poland, Italy, and Russia. All of them had offices in Ukraine, which explains how the dangerous payload arrived. Maersk, FedEx, Merck were among the victims outside the intended attack location.

According to rough estimates, the global damages from the NotPetya outbreak amounted to $10 billion. Analysts have also stated that the cyber-attack was part of the hybrid war Russia has been waging against Ukraine. Specifically, it was attributed to the Telebots hacking group affiliated with the Russian military.

Election tampering

Russia’s interference with the 2016 U.S. presidential election has been the talk of the town for years. It was a defiant campaign targeting the American political ecosystem. Hackers backed by the Russian government reportedly carried out a phishing attack against officials from the Democratic National Committee (DNC). By gaining a foothold into their email accounts, the malefactors were able to steal almost 20,000 private emails and files related to the Hillary Clinton campaign. This information became publicly available through WikiLeaks, causing reputational damage to the candidate.

In another move, the state-sponsored cybercriminals compromised the website of a state election board, thereby obtaining personal data on half a million voters. To top it off, a so-called “troll farm” headquartered in Russia’s Saint Petersburg created thousands of fake social media accounts pretending to be U.S. citizens. This way, the malicious actors attempted to influence the public opinion in favor of Donald Trump. All of these dodgy efforts are believed to have changed the status quo in the presidential election.

Industroyer

Industroyer is a unique sample of malware tailored to affect industrial control systems. It was used to perpetrate a cyber-attack against the Ukrainian electrical grid in December 2016. This incursion caused a blackout in a part of the country’s capital city Kyiv. With about 20% of the consumers being cut off power for one hour, this incident was most likely a test run of the offending code.

Industroyer includes several modules to maintain persistence and call forth serious damage. It is equipped with two backdoor components, one of which receives instructions from the Command & Control server, and the other enables the operators to reinstall the malware in case it’s spotted and removed. The data wiper element built into the infection is self-explanatory: it deletes critical files and Registry keys to render the industrial control system inoperable.

As per findings of ESET researchers who originally discovered this malware, Industroyer and NotPetya were deployed from the same server infrastructure. Close ties between the two strains suggest that they hail from the same cybercriminal source, namely the Telebots hacking crew related to Russia’s main intelligence service.

Conclusion

Some of these cyberattacks have been clearly attributed to specific governments, while others stay in the realm of allegations. There are probably many more incidents that will never gain publicity. One way or another, let’s face it: nation states added malware and hacking to their geopolitical repertoire a long time ago. As this battlefield is rapidly expanding, countries should be prepared for the emerging challenges.