The Internet is Estonia’s First Line of Defense Against Putin’s Russia

To say that Estonia and Russia have a fraught history is an understatement: The tiny Baltic state was occupied by Russia or the Soviet Union for most of the last 300 years. Like residents of the other two Baltic states, Estonians live under constant threat of Russian encroachment – even invasion.

At the same time, Estonians enjoy a high standard of living, thriving economy, competitive democracy, and plenty of internet access. Maybe the most internet access – a widely told Estonian joke is that you can walk anywhere in the country without losing Wi-Fi signal. Estonians probably live more of their lives online than anyone else in the world. Ninety-nine percent of Estonian bank transfers (which are now required by the government to be instant) happen on the internet. Estonia was the first country to hold an election on the internet.

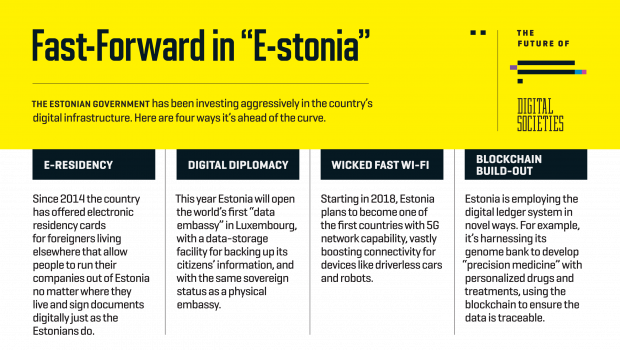

Indeed, Estonia’s economy is highly internet-oriented: Estonia has more startups per capita than most countries. The government welcomes foreign internet investment with its e-residency program, which Deloitte estimates has brought €14.4 million worth of economic benefits to the country since it started three years ago.

Source: Fortune

Estonians’ commitment to the internet is one of the country’s great strengths. But Estonia’s relationship with Russia shades everything. The internet is no exception. In fact, Estonia is the testing ground of the Russian internet skulduggery that has destabilized the world.

“Web War One”

In 2007, Estonia was the first country to be completely overwhelmed by a cyberattack. Estonia’s wired society exposed the country to the Russian cyberwarfare tactics that have become so common. Russia tested those tactics in Estonia, in the online conflict that observers have dubbed Web War One.

Estonia’s government drew the ire of Russian hackers when Estonia’s government decided to remove a controversial war memorial from the center of the capital city, Tallinn.

The memorial is known as either the Bronze Soldier or, formerly, the Monument to the Liberators of Tallinn. Soviet authorities erected the statue during the occupation of Estonia. The Soviets meant for the memorial to commemorate the expulsion of Nazi occupiers from the Baltics.

But the statue also reminded Estonians that the USSR had once again snatched independence away from the Baltic states. Estonians were certainly glad that the Soviets freed them from Nazi rule, but they were also afraid of and angered by Soviet occupation. Estonia was independent for a few decades between the Russian Revolution and World War II. But, immediately before the war, the USSR annexed the Baltics under the terms of the secret Molotov-Ribbentrop accord that Stalin’s ministers negotiated with the Nazis.

During the war, the Nazis and Soviets alternated control over the Baltic states. Both occupiers inflicted mass death and disappearance on Estonian civilians. After the war, the USSR again annexed Estonia. So, for nationalist and pro-independence Estonians, the liberation that came at the end of World War II was only in name.

That’s why the Estonian government acted to move the statue to the outskirts of Tallinn. But that move outraged the substantial ethnic Russian minority in Estonia. The USSR, as with other Soviet republics, deported hundreds of thousands of ethnic Estonians and replaced them with ethnic Russians during the war and immediately after.

Members of the ethnic Russian minority rioted when the Bronze Soldier statue was moved. (The riots are now known as Bronze Night.) The rioters were spurred on by fake news reports propagated by the Russian government and state media – and backed by Russian cyberattacks.

Estonia’s freedom is internet freedom

“For young Estonians, the internet is a manifestation of something more than a service – it’s a symbol of democracy and freedom,” says Linnar Viik, an academic who helped create Estonia’s wired culture.

“One reason why the Internet was used early on in Estonia,” Viik says, “was the government’s urge to have additional and independent windows to the international media and public. It seemed then that had someone attacked us or violated our human rights, then more than NATO tanks or McDonald’s investment Estonian independence would be better guaranteed by transparency and presence in the international media.”

Ironically, the 2007 cyberattacks proved Viik right. The revanchist Russian government of Vladimir Putin encouraged Russian hackers to devastate Estonia’s internet infrastructure with a DDoS attack. The Russians attacked specifically because Estonia was asserting its independence by relocating the Bronze Soldier. The 2007 attacks and riots were a warning to independent Estonia and its neighbors: Defy Russia at your peril.

Putin’s growing sphere of influence

Estonia was just the first country to feel the destructive effects of Russia’s special mix of chauvinist fake news and cyberattacks. The same mix has been used to expand Russia’s influence in – or even annex parts of – former Soviet republics.

Russia has repeatedly cyberattacked Ukraine since 2014, when Russia annexed parts of Ukraine. (Russia continues to support armed insurrection against the Ukrainian government in areas that have declared unrecognized independence from Ukraine.) Cyberattacks also preceded and coincided with the Russian war in Georgia, which has had similar results to the war in Ukraine.

One of the central goals of Vladimir Putin’s leadership is restoring what he sees as lost Russian prestige by exercising control of neighboring states. Estonia and the other Baltics were always some of the most rebellious and independent-minded parts of the USSR. They continue to assert their autonomy with their membership in NATO. Russia is not likely to invade the Baltics, but its continued pressure there is a warning towards the United States and the rest of NATO to stay away from Russia’s neighborhood.

Cyberattacks in Estonia were just the beginning

The cyberattacks perfected in Estonia seem to have become a permanent tool of Russian foreign policy. The fake news and cyberattack model has been used to disrupt elections and governance in states well outside the former USSR.

France’s presidential election was attacked by Russian hackers. So were Germany’s federal elections. The UK reported Russian cyberattacks at the end of 2017. You also may have heard that Russian hackers attacked United States political groups and disseminated fake news to U.S. voters during the 2016 presidential election.

Meanwhile, Estonia has done well to reinforce its cybersecurity apparatus since 2007, and the Baltic states are less vulnerable to misinformation campaigns than they were a decade ago. The Estonian government has reinforced its emergency internet access. NATO has helped the Baltic states open a cybersecurity center in the Baltics, but would likely be overwhelmed by a conventional invasion force.

Still, Russia continues to flood Western states with misinformation. Russia tested its information warfare tactics in Estonia. Estonia has set an example to the rest of the free world with its preparation for future Russian cyberattacks. The tiny country is prepared to resist Russian bullying once again. The rest of NATO can learn from Estonia’s resolute example.

About the author:

Gergely Kalman is a privacy and security advocate, and co-founder of Buffered. He was the Chief Technology Officer at Buffered until 2017 when he became Chief Executive Officer. He is passionate about privacy, security, net neutrality, and against oppression of any kind.